International & Great Northern Railroad. I&GN International Route : The Mexico-St. Louis Special, 1906. (Portal to Texas History)

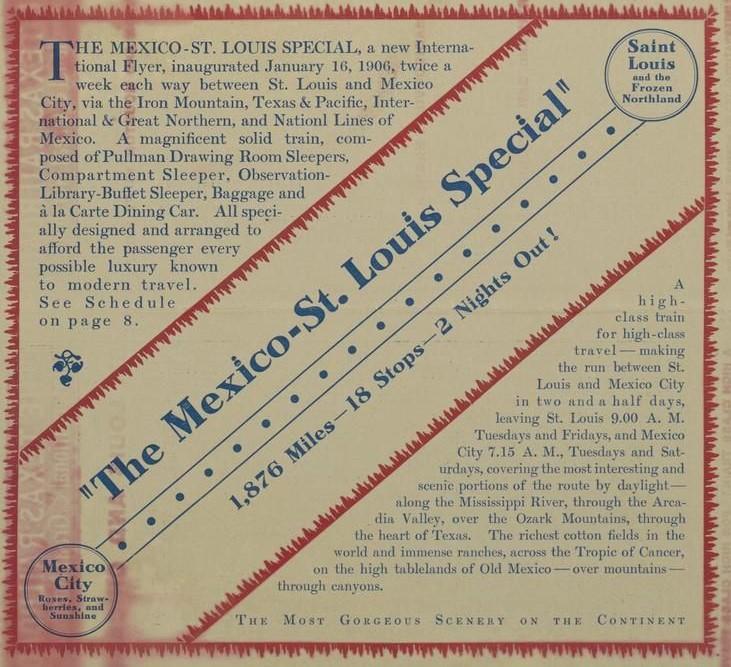

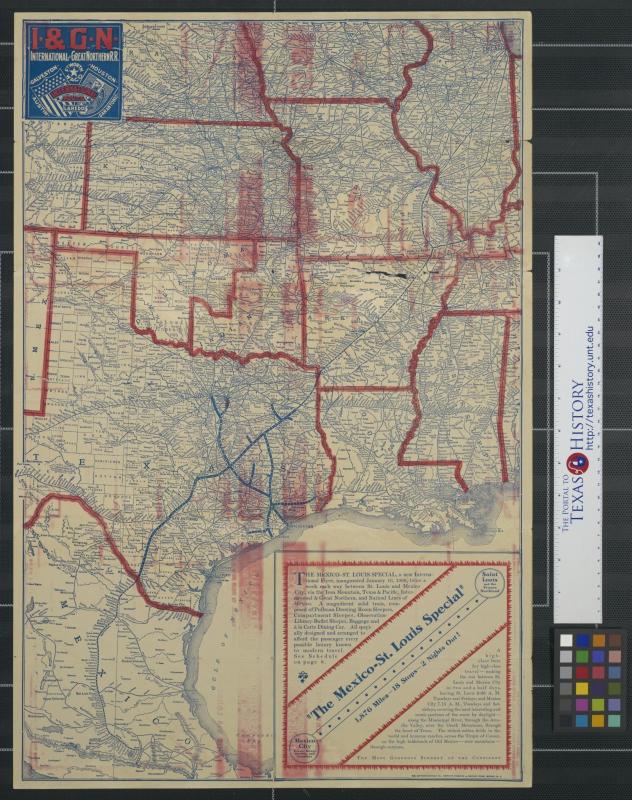

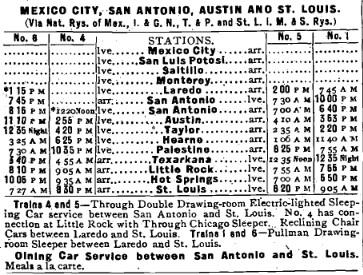

Page eight of the International & Great Northern (I&GN) Railroad Company's 1906 train schedule lists the time table for the Mexico - St. Louis Special, an American luxury passenger train line that ran between St. Louis and Mexico City twice a week between January 1906 and October 1908. The train featured high-end Pullman sleeper cars and advertised the opportunity to see "the most gorgeous scenery on the continent" during the two-night trip through the Southern U.S, Texas, and Northern Mexico. However, in October 1908, the general superintendent of the I&GN abruptly announced the end of the deluxe route in the Daily Herald of Palestine, Texas, a major hub of the railroad company, noting that “on account of conditions not being back to normal [in Mexico], we will not run a Mexico - St Louis ‘special’ this year.”[1]

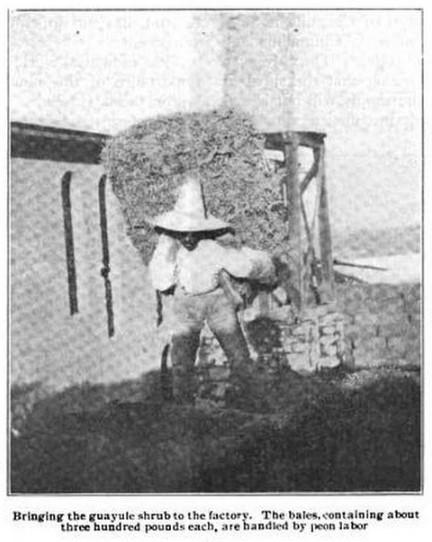

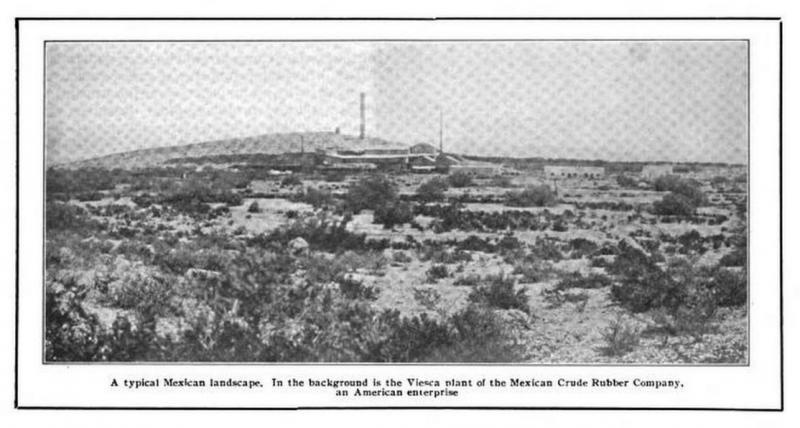

The article did not characterize the "conditions" any further, possibly implying that the reader should already be aware of the issue. Indeed, earlier that year, in June, the Palestine Daily Herald, as well as a number of other American newspapers, relayed news of "attacks" in Viesca, a desert industrial town outside Torreón on the Coahuila & Pacific Railroad, by hundreds of "bandits," whose agenda, according to the central government, was merely looting, though many newspapers relayed rumors of the start of a revolution, over two years before the Mexican Revolution began in November 1910. At the time, Viesca contained a American-owned rubber factory, the Mexican Crude Rubber Company, which extracted natural latex from the guayule bush, a labor-intensive process.[2] Similar attacks occurred later that week in Las Vacas (now Acuña) across the Rio Grande from Del Rio, Texas, and rumors spread in newspapers of larger attacks planned for Torreón, orchestrated by exiled revolutionaries operating from American cities along the border region, including El Paso, San Antonio, Austin, as well as St. Louis. Four battalions of federal Mexican military troops were sent by train to northern Mexico to regain control of government offices and repair damaged railroad track and bridges. Through railroad officials publicly denied that any track had been damaged,[3] newspapers relayed numerous first hand accounts of violence and destruction, including one American mining captialist's account of "bullets pass[ing] through the windows of [his] Pullman sleeper."[4]

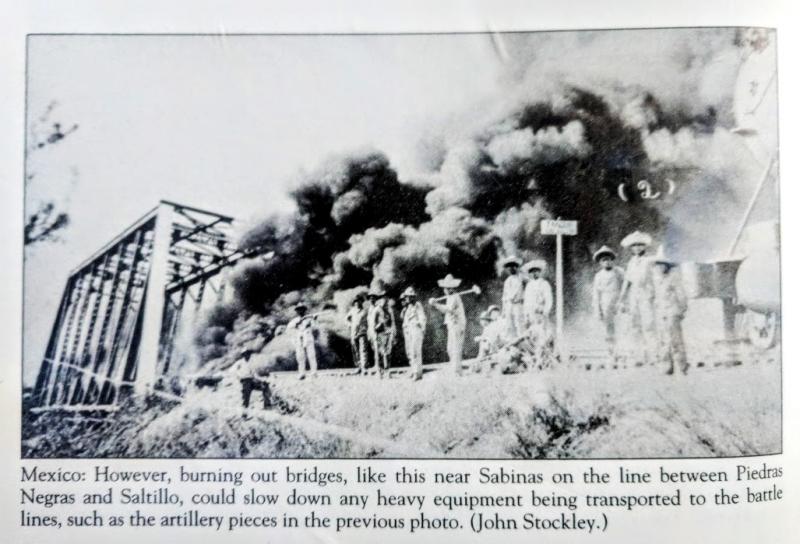

(Left) A guayulero laborer in Viesca, Coah., which saw pre-revolutionary action in 1908. The caption reads: "Bringing the guayule shrub to the factory. The bales, containing about three hundred pounds each, are handled by peon labor" (American Industries, 19). (Right) Revolting "peons" burn a railroad bridge in Sabinas, Coah. (date unknown) (Braudaway, 72)

(Left) A guayulero laborer in Viesca, Coah., which saw pre-revolutionary action in 1908. The caption reads: "Bringing the guayule shrub to the factory. The bales, containing about three hundred pounds each, are handled by peon labor" (American Industries, 19). (Right) Revolting "peons" burn a railroad bridge in Sabinas, Coah. (date unknown) (Braudaway, 72)

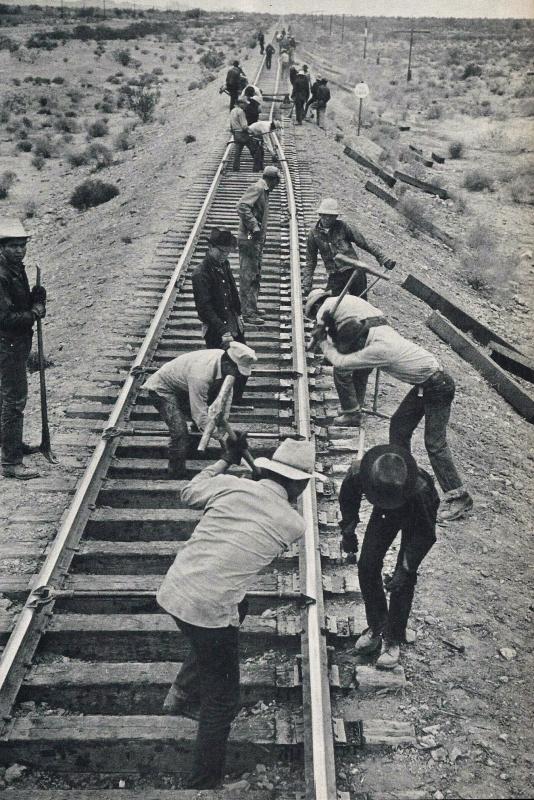

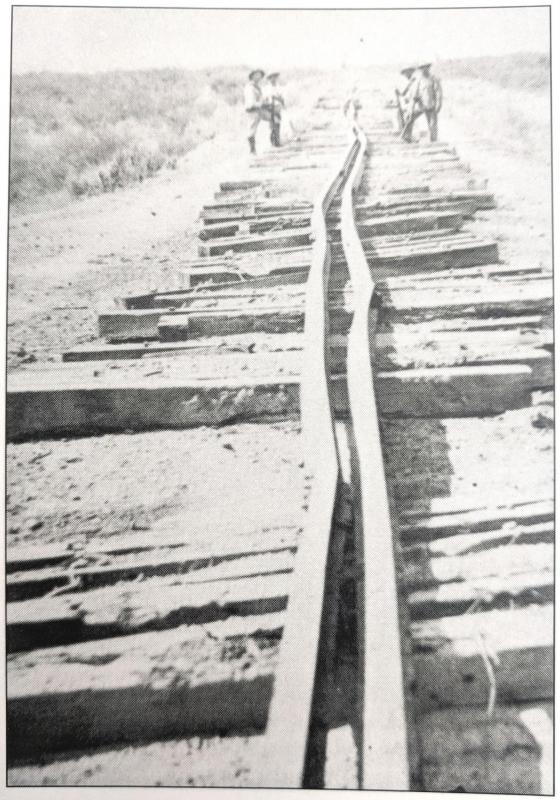

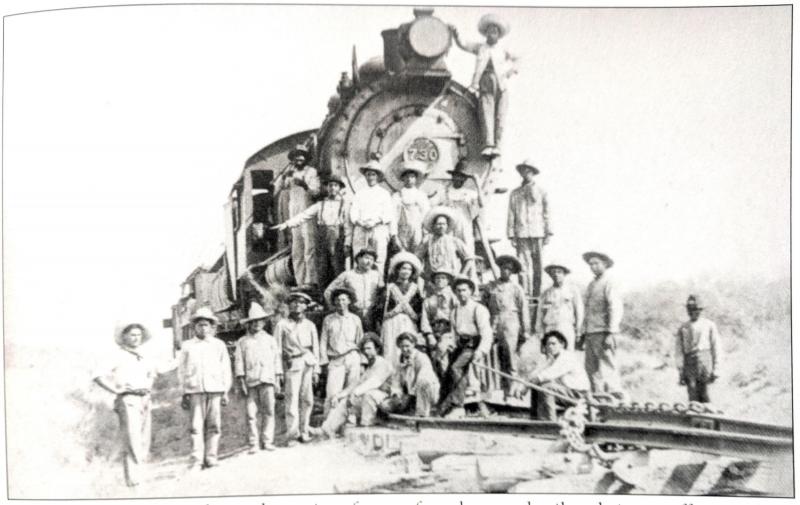

Photographs from Mexico's revolutionary period depict several tactics for hindering the movement of train-bound federal troops, including burning bridges and ripping up track using commandeered train engines rigged to squeeze rails together with chain, perhaps as a symbolic reference to the recent conversion of the Mexican National Railroad's narrow gauge lines to match the American's standard gauge lines, a modification that required traqueros manually move one side of the rail outward from Nuevo Laredo to Mexico City. The track guage conversion, which likely happened sometime before 1906[5], in fact allowed the introduction of the Mexico - St. Louis Special and other Pullman-equiped "through" lines to travel from San Antonio to Monterrey without requiring passengers transfer between trains in Laredo.

(Left) An example of a track gauge conversion effort. Here, Navajo trackmen perform a gauge conversion in the US sometime after World War II. Note the narrow gauge track in background and standard gauge track in foreground. ("Steel Gang #1 & Steel Gang #2," Metal Road: Navajo Railroad Documentary, August 31, 2017, https://metalroadfilm.com/2017/08/03/steel-gang-1-steel-gang-2/, accessed May 10, 2018). (Right) Revolutionary Mexican traqueros performing a more radical track gauge "conversion" during the Mexican Revolution (date unknown, location likely near Sabinas, Coah., Braudaway, 72)

(Left) An example of a track gauge conversion effort. Here, Navajo trackmen perform a gauge conversion in the US sometime after World War II. Note the narrow gauge track in background and standard gauge track in foreground. ("Steel Gang #1 & Steel Gang #2," Metal Road: Navajo Railroad Documentary, August 31, 2017, https://metalroadfilm.com/2017/08/03/steel-gang-1-steel-gang-2/, accessed May 10, 2018). (Right) Revolutionary Mexican traqueros performing a more radical track gauge "conversion" during the Mexican Revolution (date unknown, location likely near Sabinas, Coah., Braudaway, 72)

Revolutionary traqueros illustrating how they destroy rail line using chain tied to a commandeered engine running in reverse. (Braudaway, 72)

Revolutionary traqueros illustrating how they destroy rail line using chain tied to a commandeered engine running in reverse. (Braudaway, 72)

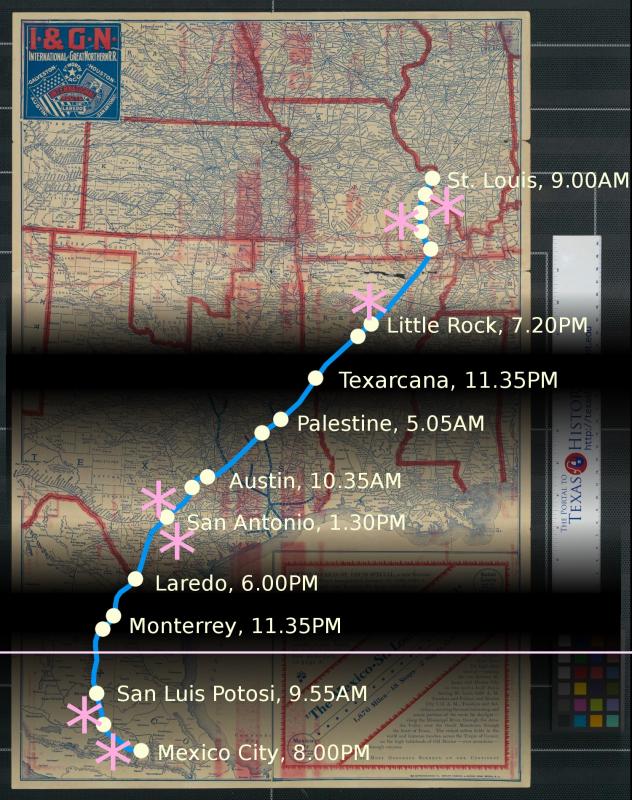

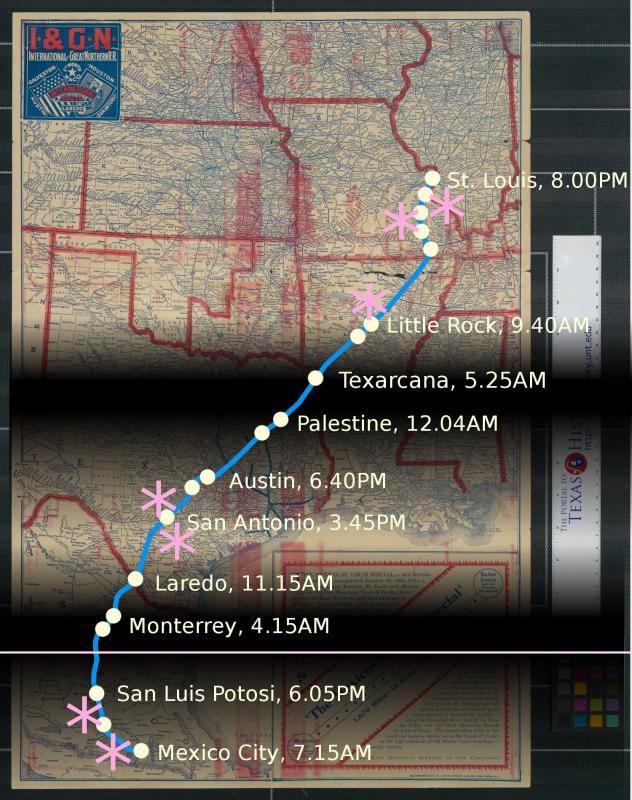

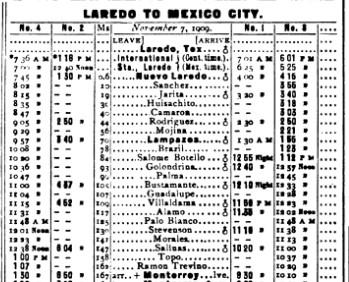

Numerous rural industrial towns similar to Viesca lay along the route of the Mexico - St Louis Special, but none of the line's 18 stops occured at these places. Along the border region the "special" stopped only in San Antonio, Laredo and Monterrey, passing dozens of smaller towns along the way, some of which operated depots out of unused railroad cars.[6] Patrons of the deluxe line likely never saw these stations since the train ran through Northern Mexico at night. The timetable of the Mexico - St Louis Special shows that both the southbound and northbound trains passed through Northern Mexico between sunset and sunrise.

(Left) Southbound. (Right) Northbound. The two-night train ride, covering the "most gorgeous scenery on the continent," featured the landscapes of Missouri, Northern Arkansas, Central Texas, and Central Mexico (pink stars). Shaded areas, Northern Texas and Northern Mexico, were traversed at night. The Tropic of Cancer is labeled with a light line.

(Left) Southbound. (Right) Northbound. The two-night train ride, covering the "most gorgeous scenery on the continent," featured the landscapes of Missouri, Northern Arkansas, Central Texas, and Central Mexico (pink stars). Shaded areas, Northern Texas and Northern Mexico, were traversed at night. The Tropic of Cancer is labeled with a light line.

Though a central marketing tactic of the luxury tourist train was to view the "most gorgeous scenery on the continent," the arid desert ecoregion of Northern Mexico was not featured. According to the advertising, the two-night trip showcased "the most interesting and scenic portions of the route by daylight -- along the Mississippi River, through the Arcadia Valley, over the Ozark Mountains, through the heart of Texas...the richest cotton fields in the world and immense ranches, across the Tropic of Cancer, on the high tablelands of Old Mexico -- over mountains -- through canyons." Through the window of the Pullman train, passengers experienced a very regularized temporal and spatial condensation of almost 3,000 miles

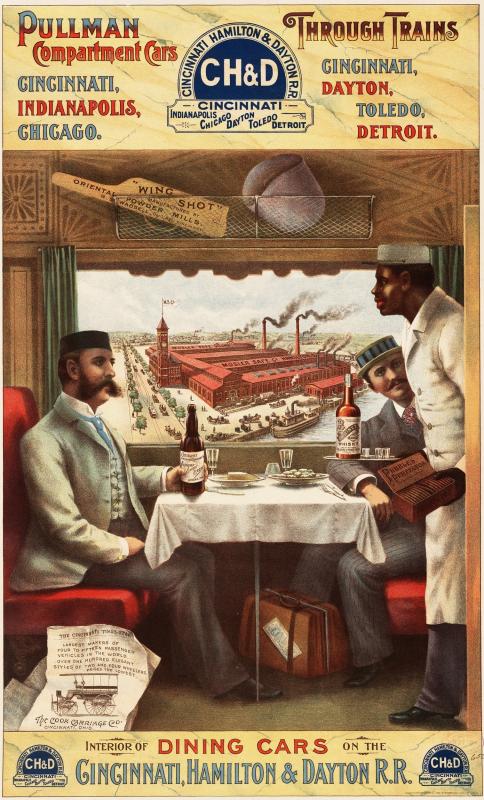

The experience of landscape in a luxury Pullman train car was considerably scripted. Passenger cars all featured observation rooms of various sorts from which patrons could sit in comfortable chairs and view the passing landscape. On the Mexico - St Louis Special the script called for the landscape of "Old Mexico," a romantic, orientalizing phrase which, among other effects, aimed to minimize the then-modern industrial elements of the Mexican landscape, such as factories and large-scale agricutlural land uses, elements that Pullman advertisements highlighted in American landscapes as symbols of progress and wealth.

Pullman manufactored a various types of passenger train cars including dining cars (below left, Library of Congress) and observation room cars (above, Library of Congress). Each car featured large viewing windows near every seat. Advertisements touted the scenery visible along the route. In a 1890s advertisement for the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton R.R. ( below left), the impressive factory of the Mosler Safe Company in Hamilton Ohio, north of Cincannati, is featured (impossibly) out the window alongside a broad treelined boulevard and a busy river port. In contrast, the landscape of Northern Mexico in the 1900s and 1910s was an arid desert dotted with rural factories, often mining smelters but also other kinds of industry such as the natural rubber factory in Viesca (below right). (American Industries, 19)

Pullman manufactored a various types of passenger train cars including dining cars (below left, Library of Congress) and observation room cars (above, Library of Congress). Each car featured large viewing windows near every seat. Advertisements touted the scenery visible along the route. In a 1890s advertisement for the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton R.R. ( below left), the impressive factory of the Mosler Safe Company in Hamilton Ohio, north of Cincannati, is featured (impossibly) out the window alongside a broad treelined boulevard and a busy river port. In contrast, the landscape of Northern Mexico in the 1900s and 1910s was an arid desert dotted with rural factories, often mining smelters but also other kinds of industry such as the natural rubber factory in Viesca (below right). (American Industries, 19)

The landscape of Northern Mexico at the turn of the century was rapidly progressing as the largest industrial region of the country, with many of the biggest factories headquatered in Monterrey. Along the web of railroad lines crossing the rural desert landscape, numerous factories were constructed to process raw minerals extracted from nearby mining sites such as those for coal and iron. Other regions, especially around Torreon, became large agricultural hubs for growing cotton and winter crops. The town of Viesca, near Torreon, hosted an agricultural-industrial hybrid: natural rubber production. Many of these factories featured distinctive smokestacks visible from great distances in the flat desert terrain.

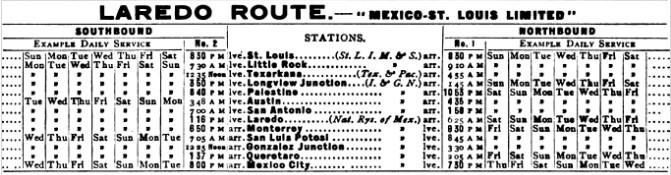

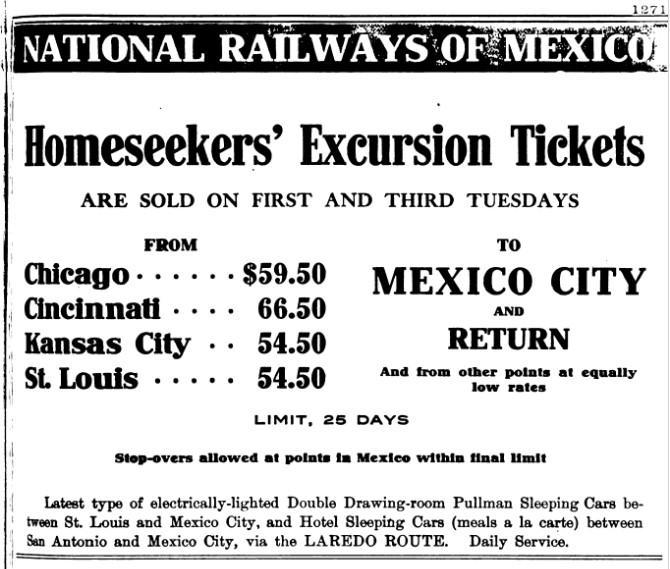

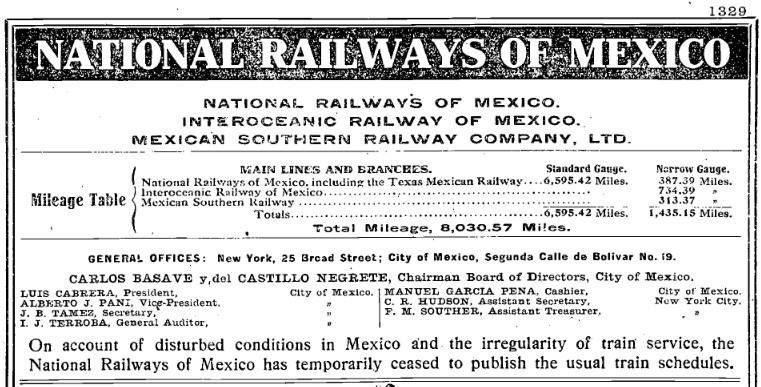

Even after the Mexico-St. Louis Special ended its short two-year run in 1908 and the Mexican Revolution began, train schedules as late as 1912 still listed time tables for "through" travel between Texas and Northern Mexico on Pullman sleeper cars, though by this time the scripting of the landscape feature visibility seems to not have be a consideration. Different regions were daylit on the southbound trains than on the northbound trains and advertisements do not mention the landscape as they once did. Additionally, the trip time between St. Louis and Mexico City capped at three nights instead of two. By 1915 I&GN service into Mexico via Laredo had ended due to the revolution.[7]

A 1912 advertisment and schedules for the Mexican National Railway, from the Official Guide of the Railways, v.44, no. 8 (Jan 1912). The three-night trip was then called the "Mexico-St. Louis Limited" and marketed as "Homeseekers' Excursions." Note the ~30 minute time difference between the "Cont. time" zone and the "Mex. time" zone.

A 1912 advertisment and schedules for the Mexican National Railway, from the Official Guide of the Railways, v.44, no. 8 (Jan 1912). The three-night trip was then called the "Mexico-St. Louis Limited" and marketed as "Homeseekers' Excursions." Note the ~30 minute time difference between the "Cont. time" zone and the "Mex. time" zone.

A 1915 schedule for the I&GN and advertisement for the Mexican National Railway showing suspended I&GN service in Mexico, from the Official Guide of the Railways, v.48, no.4 (Sept 1915). The 1915 schedule shows the note: "On account of disturbed conditions in Mexico and the irregularity of train service, the National Railways of Mexico has temporarily ceased to publish the usual train schedule.

A 1915 schedule for the I&GN and advertisement for the Mexican National Railway showing suspended I&GN service in Mexico, from the Official Guide of the Railways, v.48, no.4 (Sept 1915). The 1915 schedule shows the note: "On account of disturbed conditions in Mexico and the irregularity of train service, the National Railways of Mexico has temporarily ceased to publish the usual train schedule.

Sources

Map

International & Great Northern Railroad. I&GN International Route : The Mexico-St. Louis Special, map, 1906; Buffalo. (texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth187690/m1/2/: accessed May 11, 2018), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu; crediting University of Texas at Arlington Library.

Articles

"Are they bandits or revolutionists?," Palestine Daily Herald (Palestine, Tex), June 27, 1908. (texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth68635/m1/1/: accessed May 12, 2018), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu.

"The Crisis is Expected," Palestine Daily Herald (Palestine, Tex), June 29, 1908. (texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth68636/m1/1/: accessed May 12, 2018), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu.

"Mexicans Plan A Big Uprising This Morning," The Call (San Francisco), July 1, 1908. Accessed with subscription from Newspapers.com.

"Better Service on the I&GN," Palestine Daily Herald (Palestine, Tex), October 23, 1908. (texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth68696/m1/3/, accessed May 11, 2018), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu.

Lewis, Henry Harrison, "Guayale Rubber: A New Industry," American Industries: The Manufacturers Magazine, Vol. XI, No. 9, April 1911, p. 19, (https://books.google.com/books?id=KhVHAQAAMAAJ&lpg=RA20-PA19&ots=GFCCtoqxBi&dq=viesca%20factory&pg=RA20-PA19#v=onepage&q=viesca%20factory&f=false, accessed May 11, 2018), Google Books.

Books

Braudaway, Douglas Lee, Railroads of Western Texas: San Antonio to El Paso, Arcadia Publishing, 2000.

The Official guide of the railways and steam navigation lines of the United States, Porto Rico, Canada, Mexico and Cuba, The National Railway Publication Co., New York, NY

——— v.41, no. 2 (July 1908)

——— v.44, no. 8 (Jan 1912)

——— v.48, no.4 (Sept 1915)

Websites

"Patrimonio ferrocarrilero", Sistema de Information Cultural Mexico, http://sic.gob.mx/index.php?table=fnme, accessed May 11, 2018

"Candela Pueblo Magico Coahuila," Pueblos de Mexico Magicos, http://www.pueblosmexico.com.mx/pueblo_mexico_ficha.php?id_rubrique=601, accessed May 11, 2018

Hemphill, Hugh, "The Railroad between San Antonio and Laredo," http://www.txtransportationmuseum.org/history-lytle.php, accessed May 11, 2018

Archival Image Collections

Detroit Publishing Co., "[Chicago and Alton Railroad car interiors]," Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C., (http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016795675/, accessed May 11, 2018)

"Postcard depiction of the club car of the Illinois Central Railroad's "Panama Limited" in 1917," (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Illinois_Central_Railroad_Panama_Limited_club_car_1917.JPG, accessed May 11, 2018), Wikipedia Commons

Strobridge & Co. Lith., "Pullman compartment cars through trains -- interior of dining cars on the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton R.R.," Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C., (http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003663800/, accessed May 11, 2018)

[1] "Better Service on the I&GN," Palestine Daily Herald (Palestine, Tex), October 23, 1908; via The Portal to Texas History

[2] Lewis, Henry Harrison, "Guayale Rubber: A New Industry," American Industries: The Manufacturers Magazine, Vol. XI, No. 9, April 1911, p. 19, via Google Books

[3] "Are they bandits or revolutionists?," Palestine Daily Herald (Palestine, Tex), June 27, 1908, via The Portal to Texas History; "The Crisis is Expected," Palestine Daily Herald (Palestine, Tex), June 29, 1908, via The Portal to Texas History

[4] "Mexicans Plan A Big Uprising This Morning," The Call (San Francisco), July 1, 1908

[5] I&GN train schedules did not offer time tables for Mexican stations until 1905.

[6] "Estacion Candela", Patrimonio ferrocarrilero, SIC Mexico, http://sic.gob.mx/ficha.php?table=fnme&table_id=77

[7] Official Guide of the Railways, v.44, no. 8 (Jan 1912), v.48, no.4 (Sept 1915), v.52, no. 7 (Dec 1919)