Part 1: BARRIO SAN LUISITO

A neighborhood of Monterrey, “San Luisito,” today called Colonia Independencia, lies next to the southern banks of the Santa Catarina river, directly south of Monterrey’s centro, and macroplaza. San Luisito developed as a working-class residential district, growing alongside the booming industrial city in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, to house the burgeoning labor force. Today, Colonia Independencia or “La Indepe” as it’s called by Monterrey residents, visually contrasts with the shiny, freshly painted, skyscraper-smattered, landscape of the centro, even though it’s only a quick hop over the river. One reason for this relative lack of development is that it is a primarily residential neighborhood. This does not explain everything, however, as there are certainly other “suburban” style bedroom communities with much more commerce, multi-level construction, trees, and other trappings of an economically thriving area. While this story does not attempt to ascertain the reasons for the disparities in development of various Monterrey neighborhoods, it does paint a picture of the early years of barrio San Luisito and place it in the context of urban growth, industrial development, and urban ecology.

The city of Monterrey was limited to the northern side of the Santa Catarina river throughout its early history, yet the southern banks seem to have been populated, if only sparsely, Monterrey’s beginnings as a colonial city in the late 16th century. As early as 1596, when Diego de Montemayor first colonized, tlaxcaltecas, or indigenous people from the state of Tlaxcala, were reported to have accompanied the first colonizers, but settled on the southern banks of the river. While the actual development of the area likely occurred much later, this story may have some grain of truth to it. Apparently the other colonizers settled on the flat lands, presumably the best for agriculture, between the Santa Catarina and the source of the Santa Lucia (an arroyo or stream, perhaps seasonal), on the northern side of the Santa Catarina. This purportedly started a trend of separation between the north and south, perhaps based on who had the best available land.[1] As Monterrey grew throughout the next three centuries, the southern banks of the Santa Catarina became home to small village-like settlements, but remained only thinly populated.

Barrio “San Luisito,” and the neighborhood directly East of it, now called “Nuevo Repueblo,” became more urban contenders in the mid 19th century, as they start to show up on maps as the villages they must have been. An 1865 map, however, shows us something vastly new and different; a gridded, orderly layout of streets, drawn in dashed line to indicate future growth, projecting or planning the development of this area.[2] At this point in Monterrey’s history, many wealthy families had established themselves in Monterrey, but were fleeing to areas such as Coahuila’s La Laguna region due to an economic crisis that lasted until 1890, when such families began moving back.[3] The city was nonetheless already becoming an industrially important city throughout this period. The planned urbanization of 1865 became a reality in the next three decades, as maps from 1894 and 1901 show the same grid of roads, this time portrayed as actual city blocks at various degrees of completion, rather than the dashed lines of the 1865 map. By 1901 the economic crisis had relented, and wealthy families had returned to Monterrey to inject the economy with new capital. 1901 was also after Monterrey became connected to Texas via rail (1882), and contemporaneous with the founding of such industrial magnates as the Cervecería Cuauhtémoc (1890) and the Fundidora de Fierro y Acero de Monterrey (1900).

While little is known about exactly who lived in Barrio San Luisito, common knowledge suggests that it has always been a neighborhood to house workers for Monterrey’s growing industrial economy, and was generally less wealthy than other areas of Monterrey.[4] A common myth is that “San Luisito” was named after the migrant workers who came to Monterrey from San Luis Potosí as stone masons for the construction of the Palacio del Gobierno from 1895 to 1908.[5] The importation of such masons would have been common, as craftsmen of San Luis Potosi were masters of cantera or limestone, and had a rich architectural history of working with this material, while Northern Mexico had no such stone and therefore lacked the regional craft with this particular material. This myth has proven to be false as a creation story, however, as the neighborhood had already been referred to as “San Luis” and “San Luisito” before construction of the Palacio began, as early as 1865, in acts of the city government. Furthermore, the Palacio was not the first or last building of cantera, or limestone, the home of Lorenzo González, for example, was built in 1860, and numerous other works were built in the span of 1900-1910 including the Banco Mercantil, La Reynera building, or the Arco de la Independencia. Potosian migrants would have therefore already been in Monterrey before ___, and were undoubtedly filtering into the city (along with migrants from Zacatecas and other states) throughout the 19th century as immigration to Monterrey increased, and military conscription transplanted many families to this era.[6]

Part 2: PUENTE SAN LUISITO

As the plan to develop the southern side of the Santa Catarina marched forward, private investors and the city government realized the potential for introducing a footbridge to cross the river. Until this period, there was no method of crossing the river besides walking or paying a few cents to get pulled across on a small raft with suspension cables. Early steel and wood bridges were the first formal connections to the south of the city.[7] These bridges demonstrate the growth of San Luisito, and of its increasing legitimacy as an integral part of Monterrey’s urban fabric from the point of view of the authorities.

The first bridge to cross the river at this location, which is roughly a continuation of Calle Juarez (a major commercial and transit corridor) to the north, and Calle Queretaro to the south, was called Puente Escobedo, built by the Compañia de Tranvias de Monterrey in the late 1800’s. It changed hands multiple times, bought by the Ferrocarriles Urbanos de Monterrey and then by the city in 1899.[8] It was built from wood, and therefore burned down easily when it caught fire in 1903. This early bridge was wide enough many vendors to establish themselves in the market stalls that flanked the central passageway, and for mules to ride through, bringing visitors in wagons to the sanctuary of the Virgin of Guadalupe which was, and still is, a peregrination destination. This made the bridge a popular destination for the working-class residents of San Luisito, who could shop in the market for affordable goods, or watch the spectacle of the wagons riding by.[9]

After this disaster, the city put out a call for others to build a new bridge, and two businessmen, Fortuno V. Villareal and Jenaro Dávila were licensed to build the project that would become Puente San Luisito in December 1903. In 1905, Villareal built a steel bridge, engineered by the Compania Fundidora de Fierro y Acero de Monterrey, which was built by the firm Mackin y Dillon. By 1907, however, this bridge, too, burned down. An insurance payment from the Home Insurance Co. of New York, however, helped Villareal to fund a second version of the bridge, the final version of the Puente San Luisito.

This version of the bridge was built in two parts; the structural base and the upper covered market structure. The base was built by the Topeka Bridge and Iron Company, from Kansas, and was built of reinforced concrete, which was a new and novel technology at the time. Alfred Giles, an English architect who had established himself in San Antonio and produced many prominent works for the wealthy industrialists of Monterrey (designing many of the aforementioned works of cantera stone, was the project architect. Similar to the previous wooden bridge, there were market stalls on either side of the thoroughfare. It was inaugurated on October 8, 1908, and was immediately a successful market and bridge.[10] This bridge marks therefore not just the legitimacy of the southern districts as part of the growing city, but also a desire to imbue this corridor with the same aspirations of monumentality and progress, albeit at a more modest scale, that its architect and materials brought to the project. There was clearly a desire and real impetus to both capitalize on the massive flux of residents moving across the river daily, but also to establish this neighborhood as a thriving and important part of the city. These attempts did not last long, however, as the third and final catastrophe to marr the Puente San Luisito, the great flood of 1909, essentially rendered the bridge instantly obsolete.

Part 3: THE FLOOD of 1909:

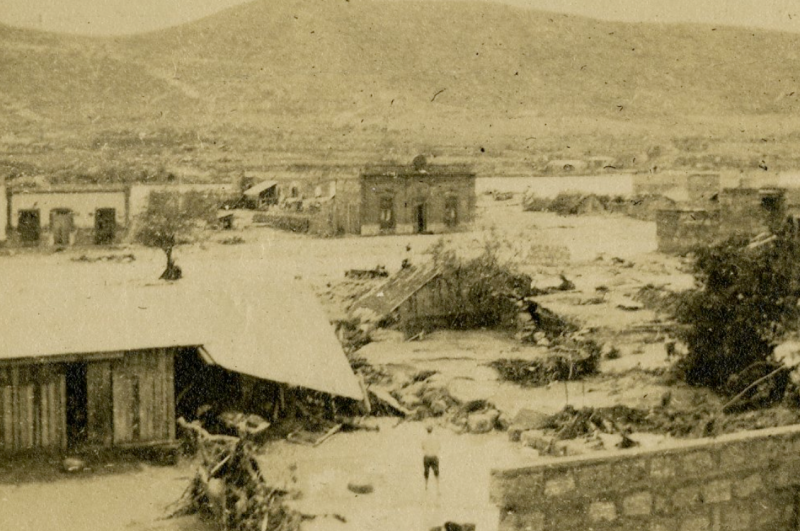

On August 27th of 1909, less than a year after the bridge was successfully inaugurated, Monterrey experienced a tremendous flood, which caused massive casualties in the city, but especially in Barrio San Luisito, where almost half of its 8-9,000 residents drowned.[11] The puente San Luisito seems to have come out of the flood as a strange victor, many photographs that remain today of the flood document the floodwaters rising in the structure as well as its emergence at the end of the flood, still standing. The bridge is therefore interesting not just as a moment of urban extension, but also as an access point into the remaining documentation of the flood itself. William Deming Hornaday, for example, who was an American journalist, editor of a trade newspaper that circulated in Mexico City, and publicity director of the Ferrocarriles Nacionales de Mexico, has an extensive archive of photographs of various infrastructural projects in Mexico, and his documentation of the Monterrey flood includes multiple photographs of the bridge, with notes that read: “Concrete structure which withstood the Monterrey flood,” and, “Reinforced concrete bridge and market house which withstood the great flood, Monterrey, Mexico”[12] His notes communicate his admiration for this new building material’s strength. Another photographer, mostly unknown except for the name “Sandoval” documented the bridge in the flood as well, with annotations to two of his photos below:

The building in the distance is the San Luisito bridge over the Santa Catarina River. It is a concrete, enclosed structure, with markethouse stalls on each side of the roadway. From the lefthand end of it to the hills on the left was formerly built up closely the town of San Luisito, which was destroyed for a width of three to five blocks from the river. See Photo No. 6, taken from the same place after water subsided.

...In the distance on the right can be seen San Luisito Bridge, shown in Photo No. 1. All the present bed of the river to the left of the bridge was formerly built up closely with houses of one and two stories...[13]

Sandoval’s comments allude to the fact that, while the bridge was not destroyed by the flood, it was made useless by the fact that the entire course of the Santa Catarina river completely changed during the storm, washing everything away in its path. The river now extended 100 more meters to the south, meaning the bridge now only reached a third of the way across the river, no longer connecting both banks. Thus, while the bridge’s survival was a triumph of engineering, it remained as a sore reminder of the flood until it was demolished in the 1950’s, as Villareal no longer had any chance of funding yet another project in this seemingly ill-fated location. An extension to the bridge, essentially a steel boardwalk, was added in 1936, but at this point it reads as a scabbed-on, ticky-tacky appendage to the remaining structure, which was still being used a market, if not as a functional bridge.[14]

Beyond these abstract notions of the bridge’s success or failure, the movement of the Santa Catarina’s trajectory had very real consequences, as the area in question was heavily populated, and was razed to nothing overnight, causing most of the aforementioned deaths. Accounts of the flood present harrowing stories of an entire city forced to watch and hear thousands of its residents being swept away or drowned. Furthermore, the flood left San Luisito without access to the rest of Monterrey for 3 days, with food and water supplies dwindling and many hungry. This certainly must have been a wake up call for Monterrey’s residents and leaders, who were witnessing a tragic event, and many of whom would suffer themselves. San Luisito was not the only part of the city that was affected - there were deaths and massive property destruction north of the river as well, just not of the same magnitude - and the rebuilding of the city would be tolling for everyone. Furthermore, rail and telegraph lines were down for days or weeks (depending on the rail line), and numerous industries, including the Fundidora, were knocked out, likely for a period of months, which must have shown the business elite that even they were not immune to such disasters[15] That said, floods like this were not unheard of in Monterrey, and continue to be a problem today. The ability of any city, politically and physically, to defend itself from floods is precarious at best, and while the flood certainly shook the city to the core and shaped future settlement patterns, the amount of infrastructural or political change it caused is as yet unknown by the author.

The causes of the flood were, in fact, well known, and perhaps avoidable. Monterrey sits in a valley, surrounded by mountains which shed water into the city through hundreds of small canyons. In Northern Mexico’s dry climate, waterways are not abundant with water all year round, but rather flow seasonally at rain events. The Santa Catarina is no exception, with flash flooding the norm and huge changes in water level seasonally. The rain event of 1909, for example, essentially rained down so much water that the river was impassable for 3 days, but soon returned to a calm state. This comes in contrast to rivers in wetter climates that experience year-round flow, and starts to explain how a flood in Monterrey could come as such a surprise. If the norm is a trickle of water, easily crossed on foot, perhaps it is easy for the public consciousness to forget what is possible.

Furthermore, Monterrey was developing quickly, and as previously mentioned, Barrio San Luisito had just sprung into existence as the gridded, urban zone it had become. It seems likely that the push to develop forced speculators and residents to overlook the potential danger of the area they were settling in, which lies directly north of many canyons as well as a hill called the “Loma Larga” all of which all drain into the neighborhood, as well as in the path of the Santa Catarina. One reporter for “El Democrato Fronterizo,” a Spanish language newspaper from Laredo, remarks on the ties between geography and speculation:

...the river of Monterrey, with a wide and very shallow bed, almost never has flowing water, and years will pass in which you wouldn’t even suspect the banks to be those of a river, but on occasion, at intervals of eight, ten, fifteen years, when a heavy and relentless downpour falls on the mountains that flank Santa Catarina, a small town to the West of Monterrey, the water picked up in this canyon falls furiously to the wide and shallow river bed, menacingly licking the banks, which rise up to two or three yards [varas] above the riverbed, without causing significant damage.

At least, that’s how it always happened until the year of 1881, when the last great flood made its mark without personal tragedy and without considerable material loss.

The authorities of the State, and municipalities, experts of the town and humanitarians, had always prohibited, with tenacity, not only that people constructed farms [fincas] in the dangerous zone, marked naturally by high walls at each edge of the river, but also the sale of lots for any type of use, within the dangerous zone.

But the current administration had no qualms dividing the banks into lots, and in the spirit of speculation, selling these lots at high prices, at the same time selling [craftyness, pretend, slyness- disimulo] for them to develop farms [fincar] on the banks of the river, as from year to year they would charge the owners of urban homesteads [fincas] located in the dangerous zone, with disingenuous [caracter] fines for violating municipal regulations, of more or less considerable amounts, which we don’t know whether or not are accounted for in the municipal treasury, nor under what guise? [caracter] they would have made the entries.

This is how, in the last fifteen years, a big business was made of putting up almost an entire city on the natural banks of the Santa Catarina river, against current orders and with full conscience of the danger to which the settlers were exposed. [16]

While this author clearly has a very strong editorial opinion, and we can’t be sure of the actual events without further investigation, the fact remains that flooding was a known threat and that there was money to be made by developing San Luisito. In fact, flooding was so common that a recent flood on August 10th of the same year, which caused little damage and a handful of deaths, reportedly set citizens’ expectations low about what the flood on August 27th might have in store.[17]

Residents were also unprepared for the flood as the majority of the damage occurred in the dark of night, and, around 9:30pm the floodwaters reached the city’s power plant, causing further darkness as there was no power to light the city. What had started out as an afternoon of rain quickly became a disaster, as cries for help began to sound throughout the city, and would be heard for the remainder of the event. Around 11pm, a huge wave caused massive damage, sweeping away almost everything in its path. By the morning of August 28th, Monterrey awoke to see several city blocks of San Luisito completely razed, as if nothing had been there before. On the 28th, Monterrey residents watched what two story buildings remained, with flood victims huddled on their roofs, slowly wash away into the current, helpless to aid their neighbors. The rain stopped on August 29th, and San Luisito remained inaccessible due to strong currents until August 30th, when a small amount of food was distributed.[18] This days long saga of loss was massively traumatic and harrowing for Monterrey’s residents, as well as those hearing of the destruction from afar.

Beyond understanding the flood itself, reports of the flood damage help us to understand what type of buildings were in San Luisito (and probably throughout Monterrey) at the turn of the 20th century. Many news reports cite there being adobe (“mud and mortar”), sillar, which in this case is a type of sandstone construction, and jacal, a wall system similar to wattle and daub, but filled with earth or rocks. Some reports mention earthen houses collapsing on their inhabitants, as they could not stand up to the rain:

“The buildings of Monterey, like those of many other old Mexican cities, are in the majority of cases composed of mud and mortar. These adobe buildings when struck by the flood veritably dissolved and in many instances the inhabitants are reported to have been caught in the falling material and rendered helpless, and drowned like rats in a trap.”[19]

Many mention that materials such as sillar or adobe could not resist the flood waters and therefore washed away:

“All the present bed of the river to the left of the bridge was formerly built up closely with houses of one and two stories, constructed of ‘sillar,’ a kind of hard clay or soft stone, which melted like sugar when the water struck it.”[20]

While less sturdy construction would certainly increase deaths due to collapsing buildings, and likely decrease the amount of evacuation time for a flood victim as buildings might wash away more quickly, it must also be noted that the flood washed away virtually everything in its path, in the areas directly adjacent to the river. The narrative that essentially blames affordable types of construction for flood damage is, arguably, not telling the whole story. The timing of this flood event, on the eve of complete industrialization, may have aided in creating a sort of tabula rasa for a city (and hemisphere) that was already rejecting traditional building techniques in favor of those more expressive of progress or modernization. As Monterrey historian Juan Miguel Casas Garcia states:”

“In the first half of the 20th century there was an interesting process of architectural addition to what had been inherited from the previous century. While in the 19th century jacal and carrizo [construction with a bamboo-like reed], adobe and wood had been predominant, starting in the epoch of Governor Reyes (1885-1909), the state’s economic boom allowed these older buildings to be substituted for ones of sillar, that is to say, a more durable material.”[21]

This was a moment of progress, and, whether consciously or not, a language developed that criminalized traditional construction in the destruction of an area that perhaps should never have been developed in the first place. The loss of these buildings was, in some ways, just as traumatic, perhaps on a different scale, as the loss of life, to the citizens of Monterrey, as the city around them completely changed form. As Sanchez and Zaragoza state when discussing the loss of buildings in the flood: “An archaic building, that of which those of the old world would have boasted, could never be more eloquent in its silence, nor could it embody with more loyalty the flowering of an epoch in which work resulted triumphant and honorable, like the old knights in a joust.”[22] While the author’s text focuses on the blow to the industrial ego of the city, what seems important from this opinion is the silent “eloquence” of these older buildings to explain the origins and growth of the city, now lost forever.

The flood also greatly impacted the industrial sector, as mentioned previously. Business must have scrambled to get on their feet again after shipments to the city were delayed, property was destroyed, relatives or employees lost, etc. Many questions remain as to how the flood affected these powerful economic and political figures in the city, and how they reacted to the flood. Did businesses invest in new, better infrastructure? Were development codes more strictly enforced? As one cynical anonymous comment on a blog post from 2013 about the anniversary of the 1909 flood would suggest, maybe less than one would hope:

“Ouff how bad for them and for us who keep doing the same, if this already has a history why is nothing done about it, we still have bad drainage systems in some neighborhoods and when it only rains a little bit these already flood and the families are those who deal with it, and the government acts as if nothing happened, they give you a burner and a little bit of food, such as soup, beans, and milk, and they think they’ve fixed everything, while the representatives etc. etc. etc. giving themselves a life of luxury what a bad situation hopefully someday these bad politics end in my country Mexico.”[23]

Of course this commentary is charged and we can’t confirm the attitude of the government towards flooding, the author clearly has personal experience of floods and their impact on the city. A news report of Hurricane Alex, which caused flooding in Monterrey in 2010 reads very similarly to the 1909 newspapers:

“Railroad Kansas City Southern… said the storm had damaged some of its rail lines, forcing it to partially shut cargo transport in several northern Mexican states…. Many businesses in the city, which has the highest per capita income in Mexico and is home to drinks giant Femsa and global cement maker Cemex, shut down as authorities closed bridges over the Santa Catarina river, usually bone-dry but surging on Friday… Tens of thousands of homes were without water and electricity on Friday and many huddled in shelters.”[24]

Hurricane Alex caused much damage in San Pedro Garza Garcia, Monterrey’s wealthiest suburb, showing that there is not a completely linear correlation between flood-prone zones and economic insecurity, but the event nonetheless shows that flooding still is, and always will be, an issue for Monterrey due to its location.

Today La Indepe is a vibrant part of Monterrey, even if a more downtrodden one than the centro directly to its north. While the puente San Luisito was demolished in the 1950’s, today there is a modern footbridge, nicknamed “Puente del Papa” as the Pope gave a speech near its base in 1979.[25] Standing on the footbridge, one gets a full view of Monterrey; its skyscrapers gleaming to the north, barely able to contain themselves from jumping right out of the opulent urban fabric. To the south, one sees the seemingly infinite residential growth, the homes of the regiomontanos (people from Monterrey) who make the city work every day. While much has changed in the city, the traces of early settlement are still very evident, and understanding where they came from will only give us a richer understanding of Monterrey today.

[1] Aparicio Moreno, Carlos Estuardo, María Estela Ortega Rubí, and Efrén Sandoval Hernández. "La Segregación Socio-Espacial En Monterrey a Lo Largo De Su Proceso De Metropolización." Región y Sociedad 23, no. 52 (2015). P 179.

[2] Casas Garcia, Juan “Del Barrio San Luisito a la colonia Independencia.” In Colores y Ecos De La Colonia Independencia, ed. Camilo Contreras Delgado. 1st ed. Tijuana, B.C., Mexico;Monterrey, N.L;: Municipio de Monterrey, Museo Metropolitano de Monterrey, 2010.

[3] Mora-Torres, Juan. The Making of the Mexican Border : The State, Capitalism, and Society in Nuevo León, 1848-1910. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001. Pp. 67-69

[4] Aparicio, et. al.,; “Colonia Independencia” wikipedia page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Independencia,_Monterrey ; Elías, Jorge, “Una Semana Siniestra en Monterrey, Agosto 21-28 de 1909 7/8 (Viernes y Sábado),” Leoncillo Sabino: Las cosas que veo y que me miran (blog), August 11, 2016. http://eliasjorge4.blogspot.com/2016/01/una-semana-siniestra-en-monterrey.html; and Casas Garcia

[5] Aparicio, et. al., p185; Casas Garcia, p19

[6] Casas Garcia, p18-21.; Sandoval Hernandez, Efren and Rodrigo Escamilla. "La Historia De Una Colonia, Un Puente y Un Mercado. La Pulga Del Puente Del Papa En Monterrey." Estudios Fronterizos 11, no. 22 (2010): 157.

[7] Cazares, Eduardo, “Primer Puente San Luisito,” Diario Cultura: Política, Cultura, e Historia, May 19, 2012, http://www.diariocultura.mx/2012/05/primer-puente-san-luisito/; Sandoval, et. al. ; It seems certain that rail bridges must have crossed the river by this point, so these hypothetically could have been crossed by pedestrians willing to make that trek. According to Sandoval, et. al., automobile bridges were not introduced until the 1950’s.

[8] Casas Garcia, Juan Manuel, and Rosana Covarrubias Mijares, “Alfred Giles, Arquitecto del Progreso,” in Monterrey a Principios del Siglo XX: La Arquitectura de Alfred Giles, ed. Lucinda Guttiérrez, Gabriela Pardo, Magdalena Graham. Monterrey, N.L.: Museo de Historia Mexicana: Gobierno del Estado de Nuevo Leòn, 2003. P 94.

[9] Sandoval, et. al. P 165-66

[10] Casas Garcia and Covarrubias Mijares, p97

[11] Sánchez, Oswaldo and Alfonso F. Zaragoza. La inundación En Monterrey: Agosto 27 y 28 De 1909. Monterey, N.L. [Mexico]: A. Pérez Sierra, 1909, p6.

[12] 1975/070-725, William Deming Hornaday photograph collection. Archives and Information Services Division, Texas State Library and Archives Commission; For biographical information on Hornaday, see the William D. Hornaday Photograph Collection at the Texas State Archives finding aid: https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/taro/tslac/60011/tsl-60011.html.

[13] “Sandoval, Fot. ‘Inundación de Monterrey,’ 1909.” Miscellaneous Photographs [Box 4, Folder 055], Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas at Austin.

[14] Casas Garcia and Covarrubias Mijares, p101.

[15] “The Daily Express” San Antonio newspaper, August 29-September 1, 1909.

[16] “El Democrata Fronterizo,” (Laredo, Tex.) Vol. 10, No. 608, Ed. 1, Saturday September 11, 1909, p2.

[17] Sanchez and Zaragoza, p9

[18] Ibid. pp13-16.

[19] “The Daily Express,” August 29, 1908.

[20] Sandoval, Fot.

[21] Casas Garcia, p30.

[22] Sanchez and Zaragoza, p.20

[23] Téllez, Fermín. “A 100 años de la Inundación de 1909,” Monterrey, Mexico por Fermín Téllez (blog), August 27, 2009, http://fermintellez.blogspot.com/2009/08/100-anos-de-la-inundacion-de-1909.html.

[24] Agency in Mexico and Telegraph Reporter, “Hurricane Alex Brings Monterrey to a Standstill,” The Telegraph, July 3, 2010, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/7869857/Hurricane-Alex-brings-Monterrey-to-standstill.html

[25] Casas Garcia and Covarrubias Mijares, p101.